|

| (photo: Ulf Andersen) |

Anthony Doerr is the author of the novels About Grace and the Pulitzer Prize-winning All the Light We Cannot See; the story collections The Shell Collector and Memory Wall; and the memoir Four Seasons in Rome. All the Light We Cannot See, which spent over 200 weeks on the New York Times bestseller list, is being adapted as a limited series by Netflix. Doerr's new novel Cloud Cuckoo Land (Scribner) shifts among characters in vastly different historical settings, from the 15th-century siege of Constantinople to an interstellar voyage in the far future. The characters are united by their connections to the fictive ancient Greek text "Cloud Cuckoo Land."

When I spoke to Nan Graham [senior v-p and publisher at Scribner], she indicated that Cloud Cuckoo Land originally revolved around the siege of Constantinople. How did the other characters and time periods come to be a part of the novel?

Yep, Nan is right: at first, I got obsessed reading about the confluence of disruptive technologies in the 15th century, when the printing press, compass and gunpowder all showed up in Europe around roughly the same time. Gunpowder (and the mega-cannons it inspired) helped the Ottomans breach the massive defensive walls of Constantinople, which had turned back every invading army for over 1,000 years.

But I didn't locate that spark--that bright vein you tap into where you know you've found something that can sustain a long project--until I started learning about Byzantine book culture. Thousands of ancient Greek and Roman texts only survived the Middle Ages because they were protected in libraries inside Constantinople's walls.

Because writing, as the 11th-century Iranian scholar Al-Biruni put it, is "a being propagating itself in time and space," it wasn't until I started trying to dramatize how a single copy of an ancient text tumbles through time and space that the project of Cloud Cuckoo Land began to take on real momentum.

That's when the five protagonists--Anna, Omeir, Zeno, Seymour and Konstance--came in. I wanted to show the book ricocheting through time, like a ball tripping through the pegs of one of those Plinko boards on The Price Is Right. The book comes into each character's life at a point when he or she needs it most, and so, for a time, they become its guardian, until it's time to pass the story along again.

The novel feels especially concerned with imminent disaster, whether it be the destruction of Constantinople or the ravages posed by climate change. Why did that become a recurring theme?

Well, there's an argument to be made that nearly every generation in nearly every culture has believed at some point that they were living at the end of humanity. Certainly that was the case for the Byzantines around Anna inside Constantinople in 1453: many of them came to believe that the fall of the city meant the end of human civilization.

And if, like teenaged Seymour, you spend a lot of time reading about climate change--and witnessing the lack of urgency with which we're responding to its challenges--it's hard not to feel like you're living at the end of something now.

That doesn't mean this is a hopeless novel: I hope that it's the opposite! I hope that it's about the ability of so-called "ordinary" people to act with immense courage, to transcend their own predicaments and make a difference for the people who will follow them.

In some ways, the characters' apocalyptic concerns feel especially relevant to recent political turmoil and the ravages of Covid. Have any of these events--or the unsettling atmosphere--changed how you view the themes of your book?

I'm not sure my attitudes about the project changed over time as much as they became more urgent. The seven years since I published All the Light We Cannot See have been the warmest seven years on record, and writers like David Quammen have been warning us about diseases spilling over from animal populations for longer than that. I started this book right around the time then-candidate Donald Trump said, "I believe in clean air. Immaculate air.... But I don't believe in climate change," and I finished it during a worldwide pandemic when wildfire smoke was so thick outside our windows that it was unhealthy for my kids to play outside. So, if anything, some of the book's darker preoccupations felt more and more insistent with each passing day.

How did you go about constructing the text in a way that felt period-accurate?

In a novel that moves from 15th-century Byzantium to 1950s Korea to a spaceship in the future, each time period presents its own challenges, of course. But that's the stuff I love to do and am so lucky to get to do: chasing curiosities, clunking around in libraries, looking into chroniclers' accounts, reading futurists and pessimists, historians and novelists. I'm a miniaturist at heart, so collecting the details and masoning them into sentences is my favorite part.

The characters repeatedly return to "Cloud Cuckoo Land," which can serve as a balm for them in times of great distress. Is there a particular text that serves a similar purpose for you?

Any good book can in itself serve as a Cloud Cuckoo Land--a Technicolor terminus with its own rules that exists only in our minds. That those worlds sometimes feel more real and vivid than our real world--that's the true magic of reading, writing and storytelling. The texts of so many writers serve that purpose for me: Anne Carson, Mary Ruefle, Marguerite Yourcenar.... In terms of this novel, I found myself often going back to the Odyssey and the Iliad. Yes, they are books from an alien time, full of violence and strangeness, but then you come across a Homeric simile like this one, when a child soldier dies a pointless death:

As a garden poppy, burst into red bloom, bends,

drooping its head to one side, weighed down

by its full seeds and a sudden spring shower,

so Gorgythion's head fell limp over one shoulder,

weighed down by his helmet.

(Book 8, lines 349-53)

You hear the voice of a bard 3,000 years gone reach through time, link life--a bright, blooming poppy--with death, and it moves you; you feel recognized; you feel less alone.

The book can be read as a paean to storytelling. Do you think there are ways in which even dedicated readers undervalue the importance of storytelling and what it can accomplish?

As far as we know, storytelling is the one thing our species can do that others can't. And look what we've done with it! We've constructed empires, built global religions, cut through continents, fished out oceans, performed symphonies over Zoom. Books are astonishing pieces of technology, able to transcend space, time, and death, and those of us who are lucky enough to read them are so privileged to get to spend some hours of our days entering other lives, other worlds, other histories.

Apparently, Machiavelli, before he'd begin an evening of reading the classics, would take off his dirty clothes from the day, put on his finest duds and, in his words, "for the space of four hours I forget the world, remember no vexation, fear poverty no more, tremble no more at death: I pass indeed into their world." Sometimes I feel that's how I should approach every hour that I'm lucky enough to spend with books: with that sort of reverence. --Hank Stephenson

It's easy--and understandable--to look at the effects of climate change and slip into a dark, hopeless mood about the future of the planet. Books like The Uninhabitable Earth by David Wallace-Wells (Tim Duggan Books, $18) and Losing Earth by Nathaniel Rich (Picador, $16) have sold well, warning about the near-apocalyptic consequences of climate change. But it's important to keep a sense of perspective. These two titles, for example, are written by journalists, and do not necessarily represent consensus views among climate scientists and activists. In fact, in influential climatologist Michael E. Mann's The New Climate War (PublicAffairs, $29), he strongly criticizes both books, arguing in his chapter titled "The Truth Is Bad Enough" that The Uninhabitable Earth in particular plays into a narrative of "doomism" that "arguably poses a greater threat to climate action than outright denial."

It's easy--and understandable--to look at the effects of climate change and slip into a dark, hopeless mood about the future of the planet. Books like The Uninhabitable Earth by David Wallace-Wells (Tim Duggan Books, $18) and Losing Earth by Nathaniel Rich (Picador, $16) have sold well, warning about the near-apocalyptic consequences of climate change. But it's important to keep a sense of perspective. These two titles, for example, are written by journalists, and do not necessarily represent consensus views among climate scientists and activists. In fact, in influential climatologist Michael E. Mann's The New Climate War (PublicAffairs, $29), he strongly criticizes both books, arguing in his chapter titled "The Truth Is Bad Enough" that The Uninhabitable Earth in particular plays into a narrative of "doomism" that "arguably poses a greater threat to climate action than outright denial." Mann's point is not that the problems facing us are simple to overcome, but rather that apocalyptic or misleading narratives might serve to foster hopelessness or point the arrow of blame at the wrong culprits. He argues that Losing Earth places the onus on human nature for failing to tackle climate change in the 1980s, rather than on Republican politicians or the fossil fuel industry, which plays into unhelpful narratives "deflecting responsibility from corporate polluters to individual behavior."

Mann's point is not that the problems facing us are simple to overcome, but rather that apocalyptic or misleading narratives might serve to foster hopelessness or point the arrow of blame at the wrong culprits. He argues that Losing Earth places the onus on human nature for failing to tackle climate change in the 1980s, rather than on Republican politicians or the fossil fuel industry, which plays into unhelpful narratives "deflecting responsibility from corporate polluters to individual behavior." Readers trying to combat climate despair might be better served by The New Climate War or Paul Hawken's Drawdown (Penguin, $23), which make up for what they lack in writerly flair with their focus on effective ways to limit the impact of climate change. The worst scenarios envisioned by The Uninhabitable Earth aren't inevitable--some of them aren't very likely--and individual agency, particularly in pushing for political action, still exists. Still, books like Losing Earth and The Uninhabitable Earth can be instructive, as long as they are read with perspective. --Hank Stephenson, manuscript reader, the Sun magazine

Readers trying to combat climate despair might be better served by The New Climate War or Paul Hawken's Drawdown (Penguin, $23), which make up for what they lack in writerly flair with their focus on effective ways to limit the impact of climate change. The worst scenarios envisioned by The Uninhabitable Earth aren't inevitable--some of them aren't very likely--and individual agency, particularly in pushing for political action, still exists. Still, books like Losing Earth and The Uninhabitable Earth can be instructive, as long as they are read with perspective. --Hank Stephenson, manuscript reader, the Sun magazine

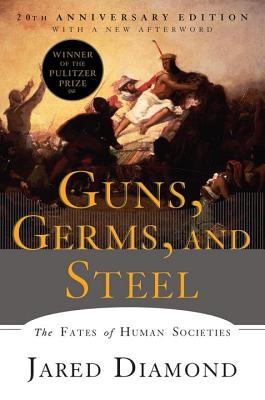

Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies (originally published in 1997 as Guns, Germs and Steel: A Short History of Everybody for the Last 13,000 Years) by Jared Diamond (W.W. Norton) won the 1998 Pulitzer Prize for general nonfiction. The book examines why Eurasian and North African societies survived and expanded over so much of the world at the cost of other cultures. The first reason was a series of positive feedback loops caused by denser human populations and corresponding agriculture, which necessitated a complex division of labor. Eurasian proximity to a wider array of livestock also gradually exposed them to more diseases over time rather than the sudden affliction of smallpox and measles on indigenous American people. Highly organized states with greater interchanges of people and ideas fostered conditions for advanced technological development capable of producing guns and steel.

Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies (originally published in 1997 as Guns, Germs and Steel: A Short History of Everybody for the Last 13,000 Years) by Jared Diamond (W.W. Norton) won the 1998 Pulitzer Prize for general nonfiction. The book examines why Eurasian and North African societies survived and expanded over so much of the world at the cost of other cultures. The first reason was a series of positive feedback loops caused by denser human populations and corresponding agriculture, which necessitated a complex division of labor. Eurasian proximity to a wider array of livestock also gradually exposed them to more diseases over time rather than the sudden affliction of smallpox and measles on indigenous American people. Highly organized states with greater interchanges of people and ideas fostered conditions for advanced technological development capable of producing guns and steel.